Why Getting Signed Is Only Half The Battle

“Something that was once my passion became my torment” – Hardy Caprio.

Introduction:

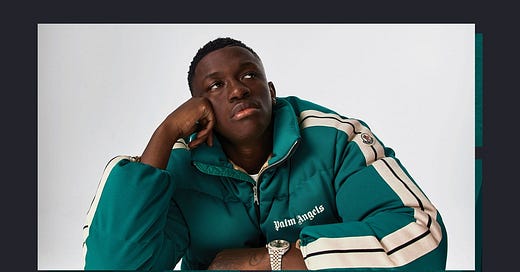

While I was in secondary school it seemed inevitable that Hardy Caprio, aka. Hollywood H, would drop another banger just in time for the summer holidays. For many people my age, his music was part of the soundtrack to our adolescence, alongside other “Afroswing” artists such as J Hus, NSG, Kojo Funds, Mostack, Not3s, Yxng Bane, Belly Squad, Fuse ODG and frequent collaborator One Acen (to name a few). He was on the cusp of mainstream success, with the Guardian commenting in 2018 that the star’s “future looks as assured as his performance[s]”. Last month he tweeted on X, formerly known as Twitter, venting about continued issues with his former label Virgin EMI. After 6 years in the limelight, it seems that his career never saw the heights it was destined for with Hardy still yet to drop his debut album.

Where did it all go wrong?

In this blog I will explore how his career was stunted by disagreements with his label and a lack of clarity surrounding contract clauses, examining from a law and business perspective what stopped him from reaching the heights and longevity of some of his contemporaries. Hopefully, this will serve as guidance to young musicians, so that they are aware of what issues they may face when working in the music industry and can make informed decisions. I plan on writing frequent music and entertainment law focussed blogs on Substack, so stay tuned: This is FR33 Game.

The Come Up:

Born in Sierra Leone in May 1996, Hardy (full name Hardy Tayyib-Bah) was faced with the perils of conflict due to an ongoing civil war. His parents decided to relocate to the UK to give him a better life, settling in New Addington, Croydon. His upbringing was tumultuous, growing up in a council estate surrounded by the vices all too common in deprived London communities. In spite of his environment, he focussed on his music talent, captivating audiences with his ability to be both a melodic hitmaker and a witty, punchline rapper (as showcased a in freestyle over Tinnie Tempah’s classic grime song “Wifey Riddim”). Oh yeah, and did I mention he got a 1st class degree from Brunel University in Finance and Accounting?

From 2017-2019 Hardy Caprio’s chart success was perennial. In June 2017 he dropped “Unsigned” ft One Acen, which peaked at 2 on the Independent Singles Chart after being pushed by Spotify’s then Senior Editor Austin Daboh (who has gone onto become President of Black Music at Atlantic Records). This was followed 2 months later by “Super Soaker”. After being signed in late 2017 to Virgin EMI for a 3-album deal, Hardy Caprio had a slew of hit singles. 2018 opened with the gritty and braggadocio filled “Rapper” in March, peaking at 34 on the national singles chart. In June he dropped a cheeky and playful feature on One Acen’s “EIO” in June 2018, which currently has over 21 million streams on Spotify. Later that same month he released the anthem “Best Life” ft. One Acen, which dropped the same month, peaking at 26 on the singles chart.

2019 looked like it was going to be Hardy’s year, teasing on his “Lucky Me Freestyle” that his album would be out imminently. This initially looked on course to happen, with the single “Guten Tag” ft. DigDat reaching 18 on the singles charts and 6 on the Hip Hop & R&B chart – his most successful song to date. He graced listeners with a pair of features on T Mulla’s “Droptop” and Dolapo’s “Something New”, showcasing his continued versatility. With multiple chart-topping singles, it seemed he was primed to have success with his debut album.

Trouble in Paradise:

Despite anticipation, 2019 came and went without an album. It became apparent to fans that the relationship between his label was on the ropes when in 2020 he opened the video to his single “XYZ” ft. SL with a disclaimer that the label had been trying to control his creative vision. Having split with his label following discussions in late 2021, Hardy went on Chuckie’s HC Pod last year, discussing what went wrong. He detailed how the disagreements began around the time he dropped “Rapper” in 2018, with them disliking the song’s slightly less up-beat vibe (which mirrored the earlier grime songs he came up on and, if anything, showed his versatility as UK rap began to pivot into the current Drill/ Street Rap focussed landscape). This was in part due to internal changes in Virgin EMI, with the team that had initially signed him leaving for other ventures. They no longer shared a joint vison for his career, preferring to pigeon hole him into what Hardy describes as a “caricature” that would perhaps align easier with the rest of their roster, which includes more mainstream artists such as Elton John, Paul McCartney, Queen, Metallica and Bastille[1].

When asked whether the problem is the music business itself or people’s misconceptions of it, he answered “I think the problem is human nature… It’s just a reflection of [it]”. He goes onto detail how there was a general disconnect between him and senior executives, who he believes often get into the “industry being based on nepotism” rather than through their ability to relate and connect to artists. Because of this disconnect, he feels they were not able to understand his vision and the constant changes happening in the UK rap scene. Reflecting on executives who did not understand why he refused to only release pop-leaning tracks, he recalls thinking “you have no love for the music, no understanding of it”. Unfortunately, to many labels “artists are just numbers[2]”.

How exactly do these numbers break down though? Hardy spends much of the podcast imparting some of the knowledge he’s picked up during his career. He starts of by outlining a typical major label deal. When an artist signs to a major label for a £200k deal, it is effectively a £200k loan that the artist is expected to pay back in full through the revenue generated through their music[3]. Most modern deals involve an 80:20 split of excess profit once the loan is made back. This means that the label gains 80% of the profit made from songs and albums, with the artist only being left with 20% for themselves. This is making the assumption that this deal involves only the artist and label are involved, rather than a manager or other members of an artist’s team (which would further diminish the artist’s cut). At the end of all this, most artists still do not own their sound recordings (aka. Masters or Master recordings). Though this is the typical deal for an artist, it is of course possible that this agreement could be different for an established artist who has gained serious traction as an independent act and can negotiate a particularly favourable deal (as I suspect Central Cee did earlier this year when he signed with Columbia Records). Even though extremely “academically gifted”, when it came to the music business Hardy acknowledges he, like many young artists, was still an “ignorant kid”.

The disregard major labels may show to their signed artists can be further explained by looking at the industry from a wider glance. It is widely accepted that “98% of all acts signed to a major label fail[4]”, never even releasing their debut album. Major labels recoup all the money they invested on a handful of superstars that rise above the rest and go onto be worldwide superstars. In Hardy’s words “Ed Sheeran will finance everything. Adele will finance everything.” Once they realised that Hardy wasn’t going to mindlessly align with their intentions, why would they continue caring about his career, let alone his well being? In their eyes, he was not absolutely guaranteed to be a ‘superstar’.

A Game of Smoke and Mirrors:

Despite leaving Virgin EMI and releasing music independently once again, there are continued disputes between him and Virgin EMI. On September 20th this year, Hardy posted a video on X of him driving to the Universal Office (Virgin EMI is a subsidiary of Universal Music Group), in order to “speak to the appropriate contact” and “get back what was stolen” from him.

What exactly was stolen though? In an earlier thread, Hardy detailed an ongoing legal battle regarding money being taken without his consent in 2020 from his Ditto account (for context, Ditto is an independent music company which independent artists can use to distribute music and automatically collect revenue from Digital Streaming Platforms like Spotify & Apple Music ). He alleges that Archie Lamb, his former manager, and other representatives at Virgin EMI gave permission to “change… the email and password” of his Ditto account “without [his] consent”. After getting in contact with Adam Barker, Head of Universal Business Affairs, in order to return control of his account upon leaving the label, he has been met with hostility.

Rather than answer his request to return control of his Ditto account, Barker has recited a contract from Hardy’s 2017 recording agreement with Virgin EMI, which “granted EMI rights to the Existing Recordings, and entitled EMI to collect all the revenues generated by their exploitation after the start of the term of the recording agreement”. This means that all the money he made on music before he signed to EMI, from singles such as “Unsigned” and his 2 Eps, were all collected by EMI on Hardy’s behalf for the duration of his contract. This money was then meant to be shared with Hardy “in accordance with [the] recording agreement”. Barker also claims the password change was done transparently “with full knowledge” of his label representatives, even though it appears Hardy was unaware of this until recently.

The most important thing to pay attention to here is that the clause related to money coming from Ditto should only have run during the period he was signed to EMI. It appears he still does not have the password to his Ditto account. Of course, I have not read the contract itself, but it would be highly unusual for such a clause to run past his recording contract unless explicitly stated. In retrospect, this is something that should have been clearly highlighted and clarified during the discussions between Hardy and the label. If this ends up leading to legal proceedings, the label may rely on the lack of clarity in this clause as a justification for their actions. Given the huge size of Universal Music Group, they have significantly more resources and funding to throw at any potential court cases than Hardy does.

Hardy has also alleged that at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, Universal took his residuals. Residuals are a form of payment paid to artists for ongoing “streaming royalties, neighbouring royalties, digital performance royalties and sync fees[5]” (when an artist’s song is featured in a film, TV show or advert). Again, I have not seen the contract so cannot comment on whether this was contractually allowed (or what specific part of his residuals were taken), but it must have certainly put pressure on Hardy at a time of particular uncertainty for musicians, who did not know when their next pay check from touring would come. The label’s behaviour has been inconsistent and suspicious, with Hardy feeling personally attacked when the owner of EMI records allegedly said “I own you” to him over a phone conversation. I have no proof of Hardy’s claims so don’t want to speculate on the validity of this. However, I would not at all be surprised if this is true – recall the late Prince’s record label issues with Warner Brothers and the undertone of discrimination that surrounded them.

Final Thoughts:

The mantra for Hardy’s career has been “I’ve been fighting and I’m gonna keep on fighting.” However, he has recently conceded that “my life isn’t all about fighting[6]”- why should it be? After working so hard to elevate his position, provide for his family and overcome his own personal trauma, it is unfortunate that he feels what was once his safe space to express his emotions has become “a space for torment”? His fans were all eager to hear what a full body of work could have looked like. Questions rise to my mind, such as ‘If more Afroswing artists like Hardy Caprio had been allowed to drop, would Afroswing have died out?’.

This label drama raises deeper issues around accurate representation of the modern Black British experience. At the end of his discussion with Hardy, Chuckie laments that “there are different black experiences”. Each and every one of them deserves to be fully showcased, but it often feels as if the music industry is only capable of pushing one at a time. There is space for hardcore ‘road’ rappers like Blade Brown (who Hardy shouts out during the pod for his work) to coexist at the same time as laid-back, melodic artists like Hardy Caprio. I suppose it’s our generation’s job to work towards creating a more inclusive industry - the fight continues.

Contact and Disclaimer:

To all the artists out there, if you have any questions about the issues I discussed above or have suggestions for future articles, please feel free to comment below or message me on @fr33.souls on Instagram.

I want to emphasise that although this blog outlines and explains legal issues, please do not rely on this as legal counsel. I intend to share my knowledge with you but I am only a law student (not yet a qualified solicitor). When seeking legal counsel which you intend to rely upon, please consult a qualified legal professional.

[1] Virgin EMI roster - https://www.universalmusic.com/label/emi/

[2] Ari Herstand, “How to Make it in the New Music Business: Third Edition” p. 77

[3] Ibid

[4] Ari Herstand, p. 68

[5] Soundcharts Blog, How Music Royalties Work: 6 Types of Music Royalties - https://soundcharts.com/blog/music-royalties#:~:text=The%20artists%20and%20record%20labels,distributors%20also%20taking%20their%20cut).

[6] HCPod “The Industry Ruined Me” -