Intro

It’s been 2 months since Kendrick Lamar crowned himself victor in this decade’s most prolific rap beef, dissecting Drizzy Drake’s public persona in the process. His scorching smash hit “Not Like Us” has been given another breath of life since the release of the music video, which displays the Compton artist kicking it in the community he grew up in. The video makes an effort to show Kendrick interacting with regular folks, driving around town and dancing with Tommy the Clown, an LA icon known for giving kids in the hood an outlet for their emotions through dance classes, settling any mumblings that he’s this mysterious, bigger than life artists.

To the disdain of Drake and his fans, it highlights the difference between the two artists; one who authentically represents the culture he came from, and one who pimps what’s popping for personal gain. A lot of people have already made think pieces breaking down the rapper’s struggles with identity and acceptance, having grown up mixed in a Jewish suburb of Toronto and not interacting much with his African-American Dad, who lived in Memphis, Tennessee. Although a lot of his decisions may stem from childhood trauma, it’s undeniable that many of them are also influenced by Drake’s keen eye for business. Or rather, Drake’s acute awareness that he is a business.

As such, I’m going to build upon ideas I mentioned in my last post how around Drake shifted Hip-Hop towards being more commercial. However, this time I want to explore exactly how Drake gained wealth and fame at the expense of his humanity.

Aubrey the Actor

Drake’s past a child actor on the popular Canadian Kid’s TV show Degrassi is something that most Hip-Hop fans are well familiar with. After all, it’s the basis for a lot of the early disses toward him, questioning his authenticity as an MC cause he’s seemingly “soft”. In a similar way to the ghostwriting allegations, these grumblings all disappeared as Drake continued his historic run. Who cared if he used to be an actor from a relatively well-off background fronting that he “Started From the Bottom”? Every single year he put out hit after hit; girls loved him, guys wanted to be him and his peers revered him.

Despite how far removed he has come from his time on Degrassi, I feel like Aubrey never really stopped acting. In fact, I would go as far as saying that he’s been playing his most convincing role yet. To me, Drake is nothing but a character that Aubrey Graham steps in and out of, accompanied by dramatic changes in accent and behaviour (Patois/ UK Roadman Drake easily being the weirdest). Music YouTuber Volksgeist has even gone as far as to say that after playing this character for so long even Aubrey doesn’t know where the line between him and Drake is drawn. First veteran rappers like Joe Budden and Common unsuccessfully took shots trying to reveal who Drake really was, then Meek Mill infamously got bodied by Drake after exposing him for ghostwriting. It was not until Pusha T took aim that the cracks in Drake’s mask began to show. Since then, Pusha’s “Story of Adidon” has become almost prophetic in predicting Drake’s downfall as the world became aware of his character flaws, with Kendrick picking up from there and finishing off the job.

As I alluded to in my intro, I think that Drake’s decisions regarding his career are often very tactical and thought out, even if they may be driven by often vindictive personal vendettas in response to trauma. Even if you hate Drake’s music, it is difficult not to be somewhat impressed by how he’s moved in the game.

Modern Day Diddy?

Even before the disgusting revelations around P. Diddy came to light and Drake was called out for being predatory towards younger girls, I’ve long thought that two have a string of similarities. The comparison might initially sound like a stretch bearing in mind the fact that Drake is best known for his 15 year run as a world-wide hit maker, whilst Diddy has primarily been behind the scenes as a music executive working behind the scenes discovering, developing and producing for artists such as The Notorious BIG, Mary J. Blige, Jodeci, Usher, 112, Faith Evans and even Justin Beiber (to name a few). Even when Diddy did eventually dabble in making music as a solo artist only songs like “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down” and “I’ll Be Missing You” really left any mark. Despite their commercial success, both topping the Billboard 100 (being the first Hip-Hop songs to do so), there are few people that consider him a serious artists in his own regard, especially in comparison to the legends signed to his roster at Bad Boy Records.

That said, I think Drake has taken the formula laid out by Puffy and streamlined it. Rather than signing a bunch of world class artists who make their own hits, why not just get them to write and produce hits which you perform? People have jokingly described the label Drake founded with long-time producer 40 and manager Oliver El-Khatib as the “OVO Sweatshop”, since signed artists are forced to give up large amounts of their songs to Drake, only occasionally getting a chance for the spotlight to shine on their own music.

The most infamous example of this involved former OVO signee ILoveMackonnen. Mackonnen started gaining traction in 2014 after releasing “Tuesday”, a catchy and weirdly unique melodic hit that quickly caught traction in the artist’s hometown of Atlanta and gained traction on SoundCloud. Soon afterwards, Drake reached out to Sonny Digital, one of the two producers on the track (the other being Metro Boomin), asking him to put him in contact with Mackonnen so he could do a remix. Saying yes seems like a no-brainer. Whenever Drake hops on another artist’s song fans always joke about how they received the “Drake Stimulus Package”, making the song infinitely bigger than than the artists could’ve done by themselves. This was no exception, and the remix peaked at Number 12 on the Billboard 100, staying on the charts for 22 weeks and going platinum. For Mackonnen this should have been life changing; he’d gone from being an artist struggling to break into the mainstream to having arguably the biggest artists, let alone rapper, in the world take his song to new heights.

However, this feature come with consequences. Remember how I said that Drake made reached out to Mackonnen to do a remix? Well, initially Drake is rumoured to have made it appear that he was not going to charge him, only to later give Mackonnen a tough ultimatum once the song really took off on a mainstream level. The first option was that Mackonnen could pay, for arguments sake, $500k for the feature (I have no exact numbers, just basing this off the fact Drake’s Young Money label mate Nicki Minaj charges around that much). Mackonnen was still on the come up and did not have that kind of cash. The alternative was to sign a recording contract with OVO Sound (an imprint of Warner Bros. Music at the time) as part of a deal that would mean he would not need to pay for the song BUT would have contractual obligations to OVO, where at the very least the label take a significant cut of his Sound Recording royalties (read this blog for a more detailed explanation of what this means). Up until today, OVO have the rights to his first 2 albums, so it is likely they still collect royalties on all of his most popular music.

The initial contract negotiations seemed to go well, with Mackonnen being under the impression that “they were interested in [him] as an artist” and that he would be collaborating with the other artists on the roster, such as PartyNextDoor, building his career. However, things soon got more complicated once “politics” got in the way, with misunderstandings arising between Mackonnen’s manager and President of OVO Mr. Morgan around what Mackonnen could bring to the label. This could suggest that they wanted him to pen songs for Drizzy using his unique style, in a similar way to what a young The Weeknd did on the early Drake classic Take Care, claiming he gave half of his debut album to Drake. When I hear Mackonnen comment that all OVO wanted from him was a “hot song.” , it reaffirms my suspicions.

Allegedly the nail in the coffin for their relationship was when resurfaced tweets (below) that Mackonnen had written in 2011 dissing Drake offended the 6-God. There is also speculation that people in OVO also stigmatised and bullied Mackonnen for his physical appearance and sexuality, which is not too difficult to imagine although I do not have substantial proof. After this Mackonnen seemed to be shelved, getting little support and promotion for his second EP. Though Aubrey is certainly petty and at times a bully, I think the fallout in their relationship also has a cold, calculated business angle. Mackonnen didn’t want to just let his work go towards building Drake’s career, going against the primary purpose of OVO: Being a super team which supports their biggest star.

This situation was of course unfortunate for Mackonnen, who never really saw the same kind of success again. However, it reinforces my Diddy comparison in two key ways:

Like Diddy, who backed Biggie from the beginning despite his (at the time) a lack of conventional star power and commercial content, Drake has a great ear for what underground sounds have commercial viability in the future. Mackonnen was not mainstream and its surprising that someone of Drake’s stature is so tapped in to what was popping. Drake has replicated this in genres worldwide, leading to him having an infinity gauntlet of sounds to use. In my hometown of London various artists have gotten looks from Drake in ways atypical of most US based artists. For example, when UK rapper Dave was on the come up and gaining a local buzz in 2015, Drake did a remix to his first big single “Wanna Know”; Dave, then 16, had only just out his first mixtape “Six Paths”, with his debut album not dropping till 3 years later. It seemed Drake knew it was essential to build a relationship with the talented youngster, with it being suggested he also tried signing Dave to OVO Sound (which Dave declined). Compare this to how most US artists and labels interact with the Central Cee - they only wanted to collaborate with him once it was painfully obvious that he had mainstream potential and was set to go global.

Drake is just as ruthless as Diddy is when it comes to ensuring that his relationships with artists always benefit himself first. Many former Bad Boy artists have complained about not being adequately, with Mase mentioning he only got $20,000 for his publishing rights in spite of creating huge hits which lined Diddy’s pockets. A similar situation is seen with Mackonnen and Drake, with the label deal being set up to benefit Drake’s career significantly more than it did Mackonnen's. Considering that even PartyNextDoor, the most loyal and long serving OVO Sound signee, has thrown shade about having his career put on the back burner, there is clearly something happening behind the scenes. And how could we forget the aforementioned Weeknd, who Drake has had an on and off relationship with after he declined to join OVO. With his jabs like “I thank God that I never signed my life away”, it’s clear that Abel doesn’t regret his decision - he probably wouldn’t have become the global icon he is if he had signed to Drizzy.

If Diddy had started off his career as an artist (and perhaps been a little less creepy), it’s easy to imagine him being a figure in the industry similar to Drake today. As predatory as Drake’s business practices are, they have hugely benefitted his career with him being talented and charismatic enough for people to turn a blind eye as he built an empire and continued to remain relevant throughout the 15 years. But how has he used this to leverage his career?

“Lebron-Sized”

It’s no secret that superstar athletes like basketballer Lebron James get paid a tonne, with his 4-yr contract (excluding brand endorsements) being $154 million USD! So when an insider on Drake’s contract re-negotiations with Universal Music Group in 2022 compared it to what the Los Angeles Laker star made using the above quote, it was clear that Drizzy was earning big bucks. The numbers haven’t been publicly announced, but experts speculate it is somewhere in the range of $400 million or more based on the Drake’s popularity and success (he likely brings in $50 million yearly from his music, so this works out for a deal spanning multiple years).

He is certainly one of the highest paid artists still recording music in the world, if not the highest paid at the moment. It appears that Drake is using the money from his music to open up other revenue paths via private equity and venture capital investments, following in the steps of rappers-turned-moguls like Jay Z and Dr Dre (both already billionaires). These include sports/ e-sports (Overtime, Player’s Lounge & 100 Thieves), restaurants (Dave’s Hot Chicken), Financial Tech (Wealthsimple) and even Marajuana (More Life Growth Co.). His most successful side-hustle is certainly his film/ TV studio DreamCrew, founded in 2017, which has been involved in hit shows such as psychedelic teen-drama Euphoria and the reboot of the beloved London street drama TopBoy. This is not to mention endorsments and partnerships he has with titans such as Nike, which all together brings his estimated net worth to apx. $180 million (2021).

Around the time the deal was announced UMG’s 1st quarter revenue rose 21.6% (totalling $2.31 bn). Given Drake’s huge importance to Universal, label CEO Sir Lucian Grange was personally involved in the deal. It helped them pin down of their most reliable income sources, solidifying their catalog holdings. This is a trend seen across the music industry as labels recognise the importance of artists with established brands in an age where most artists will not sit down to listen to an entire album unless it is by an artist that they are already very familiar with (aka the Playlist age). Universal alone spent 1.52 billion euros on catalog acquisitions for legendary artists in all genres, including American folk icon Bob Dylan who is extremely popular with older audiences.

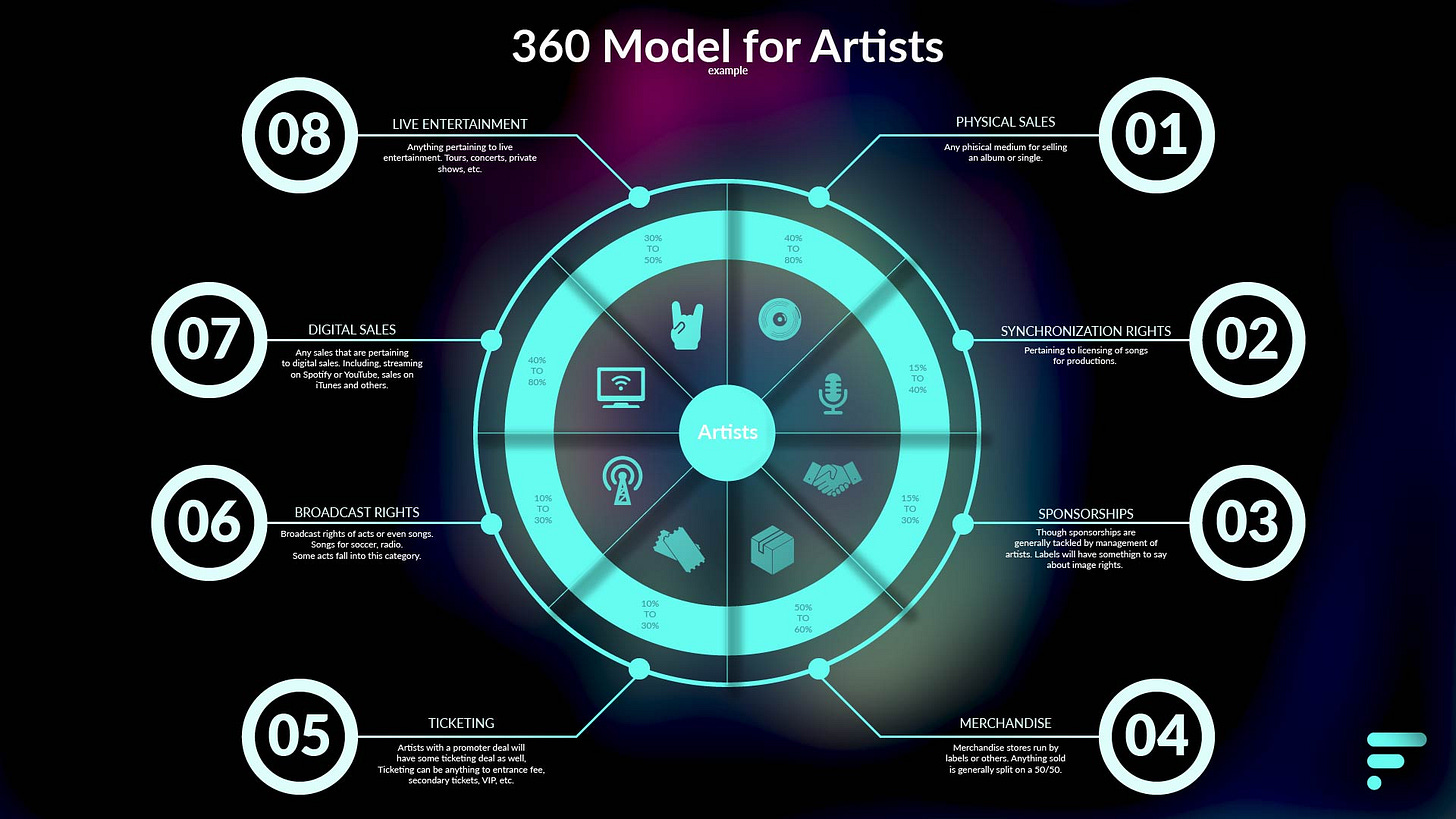

However, is there a possibility that, even as big as he is, Drake is still just the richest jester in a castle run by big corporate Kings? When announcing the deal, Lucian Grange made it a point to highlight how the deal included an “expanded portfolio” which means that Universal also has involvement in merchandising, publishing and visual media projects, on top of the standard recording contract. This sounds eerily similar to the predatory practise of a 360 deal often used to trap naive young artists into allowing their label to dig their hands into every revenue stream the artist has. In some recent episode of his podcast, Joe Budden has questioned why Drake is still putting out so many albums (apx. 2/ year) and touring continuously so deep into his career; most artists tend to slow down as they age, why hasn’t Drake? Is the contractual necessity for him to churn out music the reason why his music for the last few years has felt so uninspired? Perhaps this 360 deal means that in spite of getting a hefty monetary advance, Drizzy has to keep churning out music even if his heart is not in it. When looking at Drake’s references in his own music to his bag, such as 2021’s Lemon Pepper Freestyle, it seems that he may really be in 360 deal:

“Three-sixty upfront, it all comes full circle”

Perhaps Drake has been able to leverage himself into a better position than other artists in 360 deals have been able to based off his time in the game. Although I cannot confirm given I haven’t got details about Drake’s contract, it appears he owns his master recordings and publishing, with him suggesting as much on Certified Lover Boy. Drake’s albums post 2022 have all been under exclusive licence to UMG, as opposed to a situation where the copyright and all related intellectual property rights being directly owned by UMG. This likely means that UMG are being given permission to sell and distribute albums by the IP holder, Drake (or more specifically the label he co-founded, OVO). I’ve also heard rumblings from industry insiders (I cannot specify who for certain reasons) that Drake is on a “one-for-me, one-for-you” deal, which means that he gets to keep certain revenues made off of every other album that he makes, rather than Universal demanding vast percentages of royalties for the sound recordings on every single album he makes. Alas, I cannot confirm this so this is really just me speculating.

“M’s Count Different When Baby Divides The Pie…”

Those were some of the opening bars to the aforementioned 2018 Drake diss “Story of Adidon”, where Pusha T dissected Drake in a way we had never seen before. Though they reference the crappy contract that Drake first signed when he joined Young Money, a subsidiary of Cash Money Records, owned by the infamously shady music figure Birdman (Drake’s mentor Lil Wayne had beef with for years after Birdman failed to pay him fairly). This was something that Kendrick also used to rebuttal Drake after Drake mocked K. Dot’s deal with his former label TDE when he himself wasn’t in the best situation when he first started.

Though many do not believe that Drake is still signed to Birdman and Cash Money (details aren’t public, so again I’m speculating), Drake still has a lot of hands in his pockets. If this is the case, why doesn’t Drake just go independent? He has the fan base to sell directly to his fans, aside from additional promotion and advances on his paycheck, what can Universal really offer him? In the digital streaming age it’s not as if most of his fans are buying CDs or Vinyls which would need to be manufactured on a wide scale. Veteran entrepreneur/ music executive Steve Stout and indie-rapper Russ asked these exact questions in a 2020 discussion. Stoute reckons that if Drake was independent and wanted to drop an album, all he would need to do is “post… a picture on the ‘Gram of his new album, link in bio”, he would make “$10 million a week for f–ing 60 weeks.” Without the middlemen taking a cut, this is feasible.

However, perhaps this is something that cannot be allowed to happen, since if “Drake goes independent, the music business is over.” Conventional music labels barely survived the digital music revolution following the rise of Napster, then later Apple Music and Spotify. If the biggest artists stopped going to these major labels and instead just used their “bargaining power to negotiate a net profit split with the best deal terms and a humongous advance up front”, then major labels would really become defunct. The music industry relies on people believing in the system for it to function. It certainly seems that Drake does.

It’s top-down structure within a capitalistic market does not find profit from large numbers of people succeeding within it. In order to concentrate assets and capital for those at the top, it focusses on reliable profit rather than taking risks and being more artistic. Those that play within the system always remain at risk of being puppets tied to its twisted mechanics. Even Kendrick Lamar, in all his righteous critiquing of Drake’s desire for money and fame, is ultimately signed to UMG’s Publishing arm and, to a certain degree, beholden to the whims of Lucian Grange and the wider industry. He may have found a way to represent black people positively and be at peace within the system, but there’s a reason why someone who come across as conscious as he is will not preach on subjects like the genocides occurring worldwide - I’ll give you a hint: follow the money to find out why.

“The Industry’s Cooked, I Can See The Vibes on Ak”

The discussion around Drake and his approach towards the music industry is really just an opportunity for me to explore some of the ways that business is conducted in the industry. Drake has done extremely well by following the predatory business strategies employed by someone like Diddy, using his keen ear for trends and calculated cunning to create an ecosystem around him that has ensured he continues to stay relevant and build upon the brand (or character) that he has created.

As critical as I have been of Drake in this article, I suppose I ultimately feel kind of bad for him now that his career is dragging on for longer than it should have. Even though I was always more into music with deeper content, I cannot deny who Drake is and what he’s done. I have a lot of memories from my adolescence related to his music. Even after "Not Like Us”, if Drake plays when I’m outside, I’ll still be turning up unashamedly (don’t lie, so will you).

Of course, with the allegations around p**dophilia lurking, I am looking at his personal behaviour differently, but I do have to wonder whether, as Kendrick hinted, there’s some sort of hole that Drake is trying to hide inside that money just can’t fill.

Conclusion

This is the last time I will discuss the Drake v Kendrick beef, in part because I’m conscious that there might be a bit of fatigue around the song being present everywhere you look, but also because I want to discuss other less well-known topics within the music business. As such, I hope this gave you a comprehensive look into the power that Drake commands over the music business, as well as the repercussions of his quest for success for both himself and artists that follow suit. Until next time.

Great piece

Drake??? More like FAKE 🤥🤥🤥🤥